I recently read “Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty” by Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo. The book makes an interesting case for understanding the cycles of disease and poverty, and explains how small, incremental changes can have huge benefits for vulnerable populations. On a case study of Ugandan school system corruption, for example, embezzlement by district officials was reduced substantially by publishing school financial information in the papers. Once the information was public and officials were held accountable, corruption was reduced and schools received most of the money owed to them.

The example above implies that sometimes systems and institutions designed to provide public services fail, and when they do, work-arounds and innovative solutions are needed. Banerjee and Duflo site the three “I”s as the primary problems facing well-meaning but flawed institutions; ideology, ignorance, and inertia. The authors use these concepts to explain international development studies in third world countries, but they can also be used to explain many street design policies which have contributed to automobile domination in our public spaces and significant loss of life on our streets.

Europe vs. United States

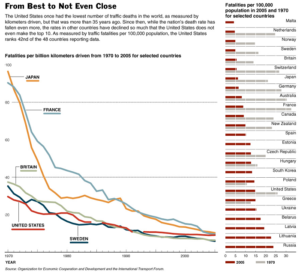

While places like the Netherlands have taken an active, grass roots stand against reducing road injuries and fatalities through safer road design, the U.S. has about 32,000 traffic deaths a year – about a 60% higher per capita fatality rate than the Netherlands. Pedestrian fatalities are also increasing. Road design isn’t even remotely within our national public discourse. We tacitly accept roadway injuries and fatalities as acceptable collateral damage for the privilege of owning and operating a personal vehicle in the most convenient way possible; with excessively wide streets and outdated roadway standards which encourage high speeds.

Still, despite its head start and that cocoon of technology, the nation has steadily slipped behind other countries, becoming comparatively one of the most dangerous places to drive in the industrialized world. -Tanya Mohn, 2007, New York Times

Many European cities focused on street design in the 20th century in order to reduce crashes. Roundabouts, pedestrian safety infrastructure, car free plazas and traffic calming became ingrained in European transportation culture during this time. Rising roadway fatalities in the Netherlanders in the 1970s spurred protests and a change in their roadway design policies. It also helps that Europe’s road network was designed before the advent of the automobile, so its streets are naturally narrower, curvier, and generally more complex to navigate. This forces drivers to pay attention and also discourages higher traffic speeds.

During this time, the U.S. made passive safety measures a priority instead. Passive safety is designed to keep the driver alive in a crash without influencing driver behavior. Passive policies made streets excessively forgiving to motorists at higher speeds, but had the unintended consequence of encouraging drivers to travel as fast as possible because, understandably, wide and forgiving roadways feel safe even at high speeds. Passive measures included bulkier cars, airbags, clear zones, and excessively wide, straight streets. The focus was protecting the driver at the expense of all other roadway users outside the vehicle.

The core idea of passive traffic safety in the U.S. came from William Haddon, a medical doctor who teamed up with Senator Patrick Moynahan and Ralph Nadar in the late 1950s and 1960s to push legislation which protected drivers at all costs without influencing driver behavior or street design.

The orthodoxy of that time held that safety was about reducing accidents–educating drivers, training them, making them slow down. To Haddon, this approach made no sense. His goal was to reduce the injuries that accidents caused. In particular, he did not believe in safety measures that depended on changing the behavior of the driver, since he considered the driver unreliable, hard to educate, and prone to error. Haddon believed the best safety measures were passive. – Malcolm Gladwell, The New Yorker, 2001

Passive Measures and the three “I”s

Passive safety in the U.S. was pushed at the expense of more holistic, design-oriented solutions which protect vulnerable road users and slow traffic. The problem isn’t mandating seat belts and air bags; they save lives. The problem is focusing on passive safety and completely ignoring design. Driver behavior should be influenced by designing slower streets, and many roadway redesign projects show the benefits of lower design speeds. Many planners and engineers still quote Haddon’s ideas, not fully understanding where the ideas came from or how the ideology has failed at creating livable streets.

Applying Banerjee and Duflo’s three “I”s concept to traffic safety isn’t much of a stretch. Here’s how they apply to institutions which have influenced road design in the U.S. during the past 50 years:

- Ideology: The U.S. has traditionally pushed passive safety measures while mostly ignoring an integrated approach to safer streets. Haddon, Moynihan and Nadar are mostly responsible for this 50 year old ideology. Lower design speeds are becoming policy at the local level, but state and national policies often lag behind. Core ideologies which have influenced road design should now be questioned: “If all traffic is going the same speed, no matter how fast, the road is safe.” “Clear, wide, obstruction-less streets are best.” “Roads are designed for cars because almost everyone drives and that’s how Americans want to get around.” These ideas are common in traffic engineering circles and are outdated at best.

- Ignorance: Getting out into neighborhoods and talking to community members to see how streets are used (or would like to be used) reveals gaps between how many transportation agencies designed streets over the past few decades and how communities would like them to function. Many surveys show people would like more pedestrian-friendly and cyclist-friendly streets even if it means slowing down traffic. Many auto-oriented design regulations often come from top-down processes which are unresponsive to community desires.

- Inertia: Many drivers have gotten so used to fast, wide, mono-use streets that anything which may interfere with free flowing traffic is deemed sacrilege. Many street regulations and policies also haven’t been updated in decades. For example, automobile Level of Service (LOS) is still used as the gold standard when comparing the feasibility of design alternatives. Designing for auto LOS means designing for the fastest speeds and widest roads possible. Long standing auto-oriented roadway culture and policies are the primary inertia forces.

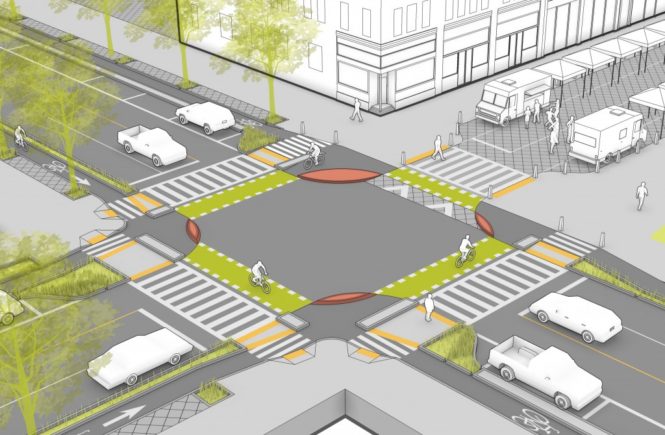

The Netherlands saw road fatalities as unacceptable and realized sensible road design was a way to make streets safer for everyone, even if it means de-prioritizing the automobile through a cultural shift. The Netherlands instituted traffic calming, shared spaces, road diets, and other measures at a national level and saw results. The country refused to accept needless carnage on its streets.

Solutions

While we can do the same in the U.S., it’s more of a challenge. The auto culture is more entrenched. Our streets are much wider and faster. Auto-oriented land uses are far more common. But we can start on the path of sensible road design by fundamentally rethinking our streets using these 5 axioms:

- Design influences behavior. Build streets as human-scaled public spaces, and drivers and pedestrians begin to act as equals. Build streets like highways, and automobiles will dominate the space and drivers will take advantage of higher design speeds by driving faster.

- Speed is the enemy. This goes against many things traffic engineers learn in school. Encouraging 30mph+ speeds on neighborhood streets may save a driver a couple of seconds but puts other road users at major risk. For every 5 MPH increase in driver speed, a property-damage only crash becomes more likely to result in an injury, and an injury becomes more likely to result in a fatality. Every single element of street design needs to communicate to drivers that speed is not acceptable.

- Material collateral damage is acceptable. Trees, curbs, narrower streets, unique intersection angles, medians and the like which slow driver speeds at the risk of low-speed collisions with a fixed object are OK. Vertical elements are good. Remember the first axiom: If drivers sense they no longer dominate the road, they will slow down and be more attentive to their surroundings.

- Human collateral damage is unacceptable. This should go without saying. Street design should be based on maximizing safety for all users at the expense of traffic speed.

- A street is a place first, a conduit second. As Mikael Colville-Andersen mentioned, we’ve gotten into the habit of engineering something that is, by nature, very organic and personal. Think of the street where you grew up. Do you describe it using level-of-service measurements? Vehicle miles traveled per day? Traffic delay? When you were eight years old, what mattered most was that traffic went slow enough in your neighborhood so you could safely walk across the street to hang out with your friends.

Many cities are now implementing local vision zero policies which attempt to change design priorities and driving culture. Washington D.C., for example, has installed traffic calming, road diets, and protected bike lanes throughout their city and has seen a reduction in pedestrian and cyclist crashes. Not only do we get safer cities with design-oriented approaches, we get more livable streets, more transportation options, and better neighborhoods. While some get this approach and innovative agencies are doing great work, the national culture is still dominated by acquiescence concerning street design. A paradigm shift in how we view roadway crashes in necessary. Changing the conversation from “Sometimes auto accidents just happen” to “This is why crashes happen and here is how we change our streets to prevent them.” is the first step.

Additional Reading:

Dr. Eric Dumbaugh: The Design of Safe Urban Roadsides. “The use of high design speeds encourages high operating speeds, which is evidenced by the fact that 75% or more of drivers in urban environments exceed posted speed limits.”

American Journal of Public Health: Trends in Walking and Cycling Safety: Recent Evidence From High-Income Countries, With a Focus on the United States and Germany

Malcolm Gladwell, “Road Killers“, The New Yorker, 2004.