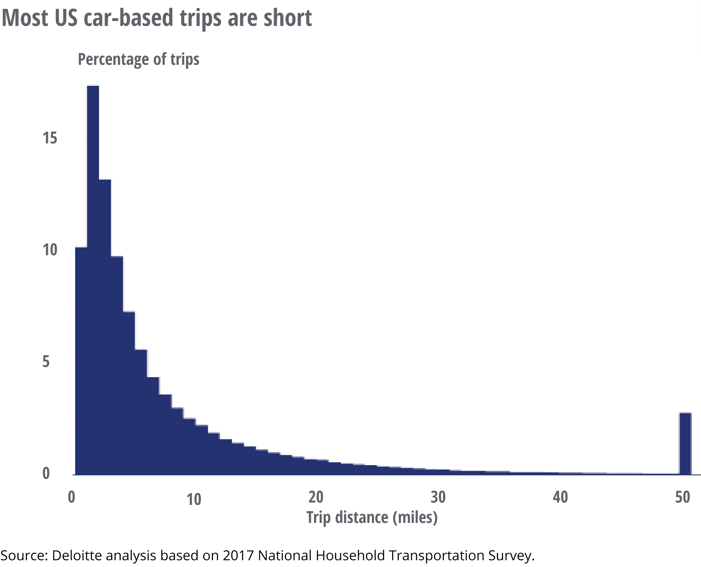

Micromobility devices have poured into American cities over the past 3 years. Go to any major city and you’re likely to see rows of e-scooters or dockless bikes lined up on sidewalks. According to NACTO, there were 84 million trips taken on shared bikes and scooters in 2018, double from the year before. With about 43 percent of all automobile trips under 3 miles, it’s no wonder more and more people are using a convenient mode that can cover shorter distances faster than walking but with less cost and hassle than driving. Riders seem to love the devices, while other people, including many government officials, have legitimate concerns about visual clutter and safety. Proactively managing micromobility programs with reasonable regulations and quality infrastructure can benefit cities, residents and mobility providers.

You may see people riding e-scooters and shared bikes in bike lanes, but you’re far more likely to see them riding on sidewalks or in traffic lanes often out of necessity given the lack of bike infrastructure in many cities. Mixing relatively low speed, vulnerable scooter riders with high speed traffic presents safety issues, however. Likewise, sidewalk riding presents another set of problems that can endanger both pedestrians and scooter riders. Crash data for micro-mobility devices is starting to be collected, and some trends have been found.

“A recent University of California at Los Angeles study found that head injuries made up 40 percent of emergency room visits caused by electric scooter crashes, followed by fractures at 32 percent. [Another] study by the Austin, Texas, health department and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 20 people were injured per 100,000 scooter trips, and 15 percent of those injured suffered traumatic brain injuries. ” – Chicago Tribune

While this sounds alarming, a closer look at the UCLA study shows that “the majority of patients [94%] were discharged home from the emergency department”, indicating that minor injuries are more common, some of which can be prevented with policy and infrastructure changes. The study also notes that most riders [94%] were not wearing helmets, which is to be expected since most people who aren’t out cycling don’t usually carry helmets with them during their daily errands.

When compared to automobiles, which are responsible for about 40,000 deaths per year, micromobility fleets are incredibly safe, but cities have an interest in doing everything possible to make these fleets even safer as they become more popular. Private providers and public agencies have a shared, mutually beneficial interest in integrating new mobility technologies into the urban fabric of our cities to create a permanent, sustainable alternative for short automobile trips. In my experience and research, this requires a combination of regulation and infrastructure.

Regulation

Many cities are aware of these safety issues and are regulating their mobility programs in various ways. Washington DC has been experimenting with various software-based speed limits on their scooters, while other cities like Hollywood, FL have banned them outright. Atlanta recently imposed an evening curfew on their fleet after several fatal crashes. There’s clearly a need for alternative mobility options, however, and micro-mobility companies have touted the environmental benefits of their fleets. Lime reported that their program has prevented 5 million pounds of carbon emissions, while other informal ridership surveys have shown at least 20% of riders would have driven to their destinations if not for micro-mobility fleets.

In my experience managing a small e-scooter fleet in South Florida, capping the number of devices was critical in creating an orderly program which balanced the needs of riders, residents and tourists. There are diminishing returns in flooding cities with too many devices. Visual clutter, including rows of scooters that have fallen over, and the likelihood of stray devices parked on private property or other inappropriate places can quickly turn the public against the program. We made sure the supply of our devices didn’t get too far ahead of demand.

Our program was also successful due to designating staging areas based on land uses and tourist attractions. Our downtown area and metro station were key staging areas, and vendors needed our approval before staging in any other areas. New locations were only approved with evidence of ridership. A speed cap of 15mph was also recommended, given that up until recently, Florida law only allowed e-scooters on sidewalks. It can be argued that regulating speeds is useful and desirable even for roadway and bike lane riding, as there are safety issues with scooters acting like automobiles in traffic lanes or bypassing bike traffic in bike lanes too quickly.

Regulation also gave us the authority we needed to be responsive to community requests. We reserved the right to impound improperly parked devices that were not relocated at our request at cost to the operator. If I received a call from a resident about an e-scooter blocking a driveway, for instance, having a cooperative vendor with clear responsibilities described in our MOU made handling such issues easier for all parties involved. Overall, a balance between fast, innovative private sector mobility and proactive public sector oversight contributed to our program’s success.

In New York , legislation is proposed to allow e-scooters and electric bikes on city streets, but it’s being reconsidered by the Governor. Pedestrian conflicts on the busiest sidewalks in the United States, a plethora of devices cluttering already-crowded streets, and excessive e-scooter speeds in bike lanes seem to be the state’s main concern. With these considerations, New York City would benefit by replicating Coral Gables’ model, but at a much larger scale, by:

- Proactively determining the placement of devices based on trip generators. Staging devices where they’re likely to be used will create less visual clutter from unused rows of e-scooters while maximizing ridership of the entire fleet.

- Assessing demand and not allowing an oversupply of devices. It’s better to incrementally increase fleet sizes based on proven demand.

- Limiting speeds of electric devices. Given that there are many novice riders and that conflicts still exist with pedestrians and other roadway users, a top speed of 15mph (about that of an average cyclist) is a good compromise between convenience and safety.

- Holding private companies accountable for proper maintenance and relocation of improperly parked devices. Agreements between private providers and municipalities should designate timeframes where providers will remove or relocate devices at the request of city staff.

Considering NYC’s abundance of bike infrastructure, a successful program could be operated if micro-mobility users and providers utilized the existing network of bike lanes. This brings us to the other major component of a successful micro-mobility program.

Infrastructure

Most American cities have a disconnected network of bike lanes. They aren’t nearly enough to meet the demand of a growing micromobility demographic. Regulation is one tool to improve safety, but it doesn’t solve the underlying issue: There’s a clear need for dedicated street space that can meet the needs of this growing user base that lies somewhere between pedestrians and automobiles. This space is a special place that isn’t as fast as automobiles, but is faster than sidewalks. It’s a space that’s vertically protected from automobile and truck traffic so that people of all ages and abilities can use it. And it’s a space that can be carved out from underutilized traffic lanes or other leftover right-of-way .

Luckily, these spaces have already been invented, and NYC already has a growing network of them. It’s called a cycle track, and there are examples of them all over the country. Given that the demand for cycle tracks is growing due to micromobility programs, there’s never been a greater need for dedicated space that meets the needs not just of cyclists, but scooter riders and future riders of yet-to-be-invented devices. Due to a broader user base utilizing this type of infrastructure, perhaps rebranding is in order. “Slow Lanes” or “Middle Lanes” better describes this space that can serve the needs of all people traveling at a speed faster than pedestrians but slower than automobiles.

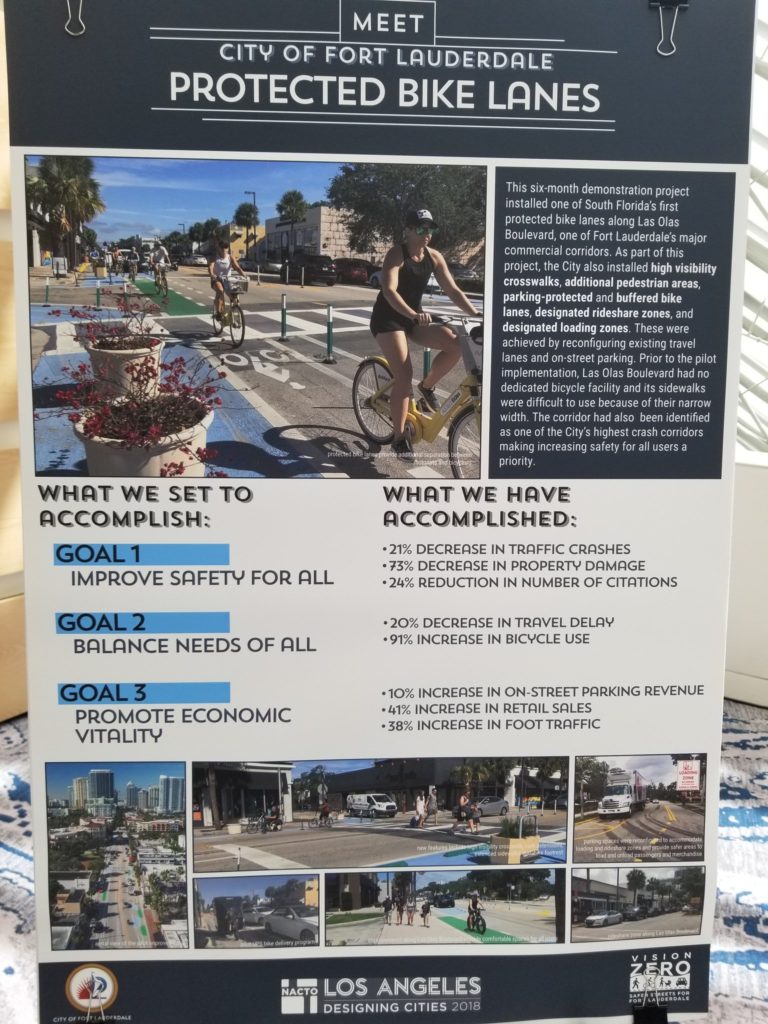

Many of these facilities have already been built. At the 2018 NACTO Conference, Ft. Lauderdale showed off amazing results of their cycle track on Las Olas Boulevard, with a 27% reduction in all crashes, a 91% increase in cycling and a 41% increase in retail sales after construction.

NYC also saw big safety benefits of cycle tracks in several longitudinal studies, with the following results after a 3-year data collection period:

- Pedestrian injuries are down by 22%

- Cyclist injuries show a minor decrease even as bicycle volumes have dramatically increased

- Total injuries have dropped by 20%

- 74% decrease in average risk of a serious injury to cyclists from 2001 to 2013

- Cyclist injury risk has generally decreased on protected bicycle lane corridors within this study as cyclist volumes rise and cyclist injures decrease (Source: NYC DOT)

If these benefits are so apparent in a pre-micromobility world, imagine if full networks of cycle tracks were built to accommodate not just a growing number of cyclists, but e-scooters, e-bikes, and future devices we can only dream of. Replacing a significant number of automobile trips under 3 miles with these modes would go a long way in meeting sustainability goals, Vision Zero goals, and creating more equitable cities that provide transportation options for all people.

An issue I heard about frequently while speaking with people throughout the country are rows of unused e-scooters blocking sidewalks. Creating designated micromobility parking areas can solve this issue. Seattle has painted designated staging areas for their fleets, and the addition of traditional on-street bike corrals can accommodate micromobility devices as well, especially newer “lock-to” programs which require all parked devices be locked to a fixed object.

Financially, it makes sense for micromobility companies to contribute to the costs of operating their devices in a safe manner. Public sector staff are needed to manage programs, and new infrastructure to accommodate scooters isn’t free. There should be a rational nexus between the operational and infrastructure burden placed on cities and what mobility companies contribute to municipalities.

Data

Somewhere between infrastructure and regulation lies data sharing between mobility providers and municipalities. LADOT pioneered Mobility Data Specification (MDS), which helps cities manage micromobility fleets, regulate where they can be staged, and track trips and other trends in real-time. Anonymized data can be shared with the public and help inform regulation and infrastructure decisions. There are privacy issues with sharing so much information, however, and some private mobility providers have pushed back on supplying such detailed ridership data. Having a good understanding of how people are using the service is the first step in creating a micromobility program that meets the needs of users, officials and other stakeholders. At the same time, the public sector also needs to be responsible for safe guarding user privacy, and state sunshine laws should be carefully reviewed as part of MDS agreements with providers.

The New Normal

Thinking of micromobility programs as extensions of traditional bike infrastructure programs can help both initiatives gain mode share in a responsible, safe way. While e-scooters may be a fad, they’re more likely a beginning of a new normal, where technology, private sector innovation and public agencies work together to fill in gaps in sustainable transportation access which have long plagued American cities. A combination of proactive regulation and multi-modal infrastructure are keys to creating successful micromobility programs. Hopefully cities across the country can leverage private sector innovation and change the paradigm of transportation for future generations.

Additional Reading:

NACTO’s “Guidelines for Regulating Shared Micromobility”, 2019. https://nacto.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/NACTO_Shared_Micromobility_Guidelines_Web.pdf

2 Comments

Good points. I think there’s a learning curve for cities in how they’re dealing with an influx of micromobility options. It seems the ones who took a “wild west”, anything goes approach are having growing pains compared to the ones who took a slower, more measured approach.