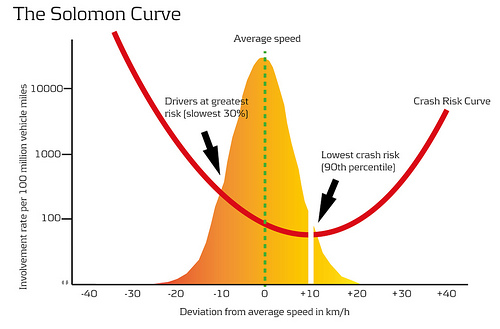

The University of Westminster recently released a cycling safety study which used travel surveys to predict future cycling crash hot spots. By recording rider information on near misses, non-injury incidents and qualitative perceptions of safety, Rachel Aldred and Sian Crosweller showed that slower cyclists experience roadways differently than faster riders. Casual riders had more near misses and perceived roadways as more dangerous.

A strong negative association between cycling speeds and incident rates per mile was apparent when comparing group means, remaining as a strong predictor variable in regression analysis. This suggests that those unable to keep up with motor traffic may have substantially more near miss experiences on a given journey.

The research shows fear of injury and automobile conflicts are major concerns for cyclists and create barriers for new riders and those unable to keep up with faster traffic. Riding in traffic on slow neighborhood streets isn’t much of a barrier to entry, but attempting to cycle in traffic on higher speed roads (which are often the only connection between major trip generators) without dedicated biking facilities poses perceived and actual risk. Another study in San Francisco shows that 86% of those who cycled at least annually had experienced a near miss, with 20% having been hit. Near misses were more strongly associated than collisions with perceived traffic risk.

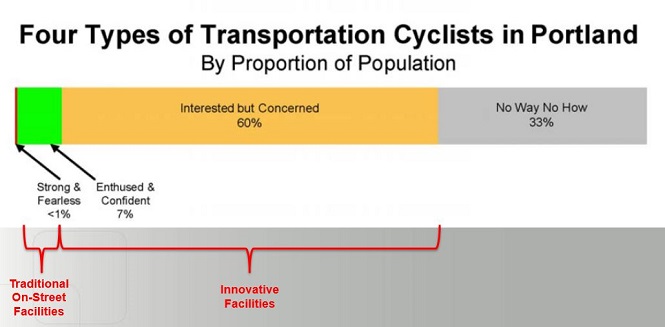

Rider surveys like these are valuable for proactively assessing the need for infrastructure improvements. Recording near misses can help inform the transportation planning process before serious injuries occur. The findings tie into Portland DOT’s “Four Type of Cyclist” chart, where a large segment of the population are interested in cycling but have concerns about safety and lack of infrastructure. Slower, less experienced cyclists may not only perceive streets as more dangerous, they may actually be more dangerous according to Aldred’s research. Due to the difference in cyclists/auto speeds and lack of separated biking facilities, slower riders may be at more risk when cycling in traffic.

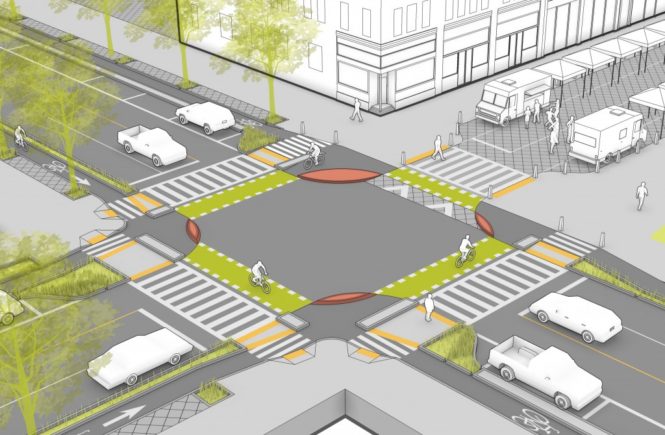

While Aldred’s paper doesn’t discuss infrastructure policy in detail, the findings infer that protected cycling facilities such as cycle tracks, buffered bike lanes and protected bike intersections can greatly improve perceived and actual safety for slower riders. In attempting to gain bike mode share and replace shorter automobile trips, cities will have to attract new riders who are unused to or unwilling to ride in traffic. Giving these riders the confidence and safety of protected facilities will go a long way in attracting broader demographics to sustainable modes, and the benefits don’t only accrue for cyclists. NYC DOT found that protected bike facilities not only improved cyclist safety but reduced crashes for pedestrians and automobiles as well.

A near miss involving an automobile can be enough to turn a future dedicated cyclist away for good. Protected facilities can go a long way in reducing such incidents and increasing bike mode shares for cities across America.