Roundabouts have been popular in Europe for decades, but have only recently seen widespread adoption in the U.S. There were less than 50 roundabouts in the U.S. before 1994. Today, there are nearly 10,000, with hundreds more being built every year. In terms of automobile traffic safety benefits and the reduction of injuries and fatalities at intersections, extensive research and real world data shows substantial safety benefits which vary depending on roundabout design. Lower maintenance costs compared to traffic signals, increased intersection capacity, and flexible designs to fit a variety of intersection types are added benefits. Less objectively, the addition of a central island allows for aesthetic improvements to what would ordinarily be an expanse of impervious asphalt. While roundabouts aren’t a panacea, and pedestrian and cyclist access issues are still being resolved through design iterations, roundabouts can improve the function and safety of an intersection dramatically.

Safety

The automobile safety benefits of roundabouts are well documented through extensive research and real world outcomes. Roundabouts tend to greatly reduce the likelihood of right-angle crashes (usually the deadliest for drivers) while also reducing speeds, two major factors in roadway fatalities. A meta-analysis of roundabout studies found that converting junctions to roundabouts is associated with a reduction of fatal accidents of about 65% and a reduction of injury accidents of about 40%. In a study of roundabouts across Minnesota, the state found a 60% to 80% reduction in fatal crashes and injury crashes after construction, with a 70%-80% reduction in right angle and left turn crashes as well. A study of rural locations showed statistically significant reductions for the total number of crashes (63%) and injury crashes (88%) when roundabouts were implemented. A New York State DOT study found that a sample of roundabouts on average reduced crashes by 47%. Many state DOT websites also describe the safety outcomes of roundabouts and provide guidance on best design practices.

TRB’s National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Report 572: Roundabouts in the United States shows varying degrees of automobile safety benefits for roundabouts depending on neighborhood type and existing traffic control devices. A study of 55 intersections with 2 years of before and after data showed that:

- A conventional, urban 4 way intersection with no traffic control had a 76% reduction in crashes when converted to a roundabout

- An urban 4-way signalized intersection had a 60% reduction in crashes after conversion

- A suburban signalized intersection had a 67% reduction in crashes after conversion

- An all-way stop controlled intersection had a crash increase of 28%

Cyclist safety in roundabouts shows mixed results, however. A study of 300 roundabouts in Denmark showed the installation of roundabouts led to a 65% increase in bike crashes and a 40% increase in injuries. A study out of Utah State University also showed that bike crash frequency increased with some larger roundabouts. The authors suggest some of the following design guidelines to reduce bike crashes:

- Encourage low traffic speeds entering the roundabout

- Where possible, design roundabouts with a single lane

- Reduce the total size of a roundabout and have larger and higher central islands

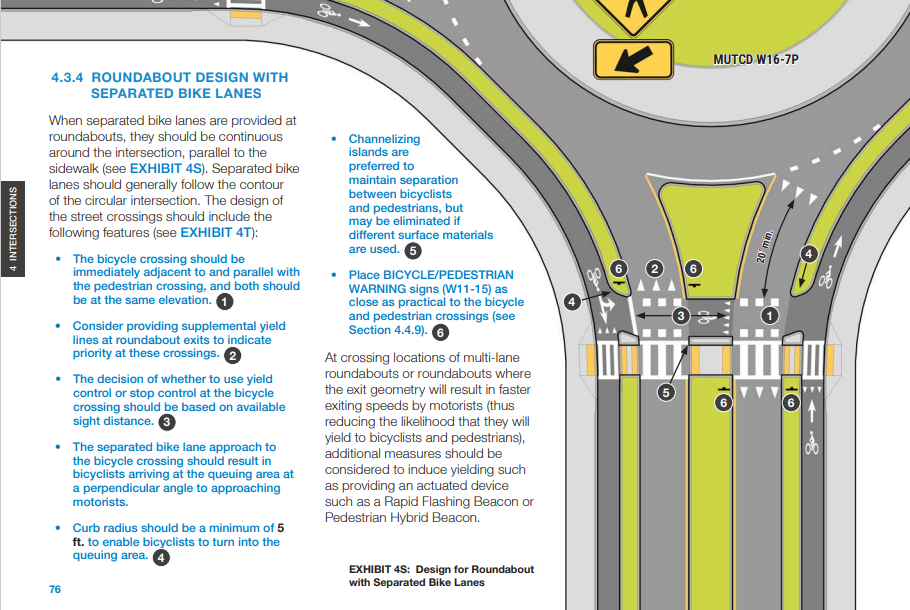

- Provide protected bike lanes on multi-lane roundabouts

Studies also suggest that painted, unprotected bike lanes within roundabouts do little to improve cyclist safety, since drivers may still be unaware of entering/existing cyclists at intersection legs. Roundabouts with protected bike lanes are an option where right-of-way permits, however.

Pedestrian safety evidence is less abundant, since little real world before and after longitudinal data has been analyzed. One study states, “In Sweden a 2000 study of vehicle-pedestrian crash data from

72 roundabouts showed that single-lane roundabouts are very safe for pedestrian compared to stop controlled and signalized intersections (about a 78% reduction in injuries)”

An often-cited study from the University of Tennessee implies there may be pedestrian safety benefits, but indicates a lack of real world data and relies on statistical models. More recent research indicates roundabouts have more conflict points for pedestrians, and may be more dangerous for slower pedestrians.

“Finally, roundabouts were thought to be safer for pedestrians than signalized intersections due to a lower number of conflict points, but the confusing multiple vectors of roundabout traffic converging into exit lanes and the frames of approaching traffic at roundabout entrances did not accurately capture the risks a pedestrian must take into account when traversing the roundabout. The data on relevant traffic showed that pedestrians had to be attentive to almost six times as many approach vectors in the roundabout as they were in the signalized intersection.”

Other design guidance shows that single lane roundabouts are safer for pedestrians compared to multi-lane roundabouts. Design principles which can improve roundabout safety for pedestrians include:

- Splitter islands with good visibility between drivers and pedestrians

- Marked crosswalks and pedestrian signs on each leg

- Sufficient horizontal deflection and roadway narrowing at legs to slow traffic entering roundabout

- RRFBs or Pedestrian Hybrid Beacons at crosswalks

- Raised crosswalks closer to roundabout entrances

Community Support and Engagement

Since roundabouts are relatively new to the U.S., it’s important to engage the community early and often during the planning process. Information on roundabout safety, aesthetics, costs, traffic maneuvers, and impacts to adjacent roadways should be presented to the community before engineering begins. Examples of existing roundabouts in the U.S. and their real world outcomes should also be discussed, since many examples now exist and can help illustrate the benefits of roundabouts. FHWA provides educational materials cities can use in their community presentations.

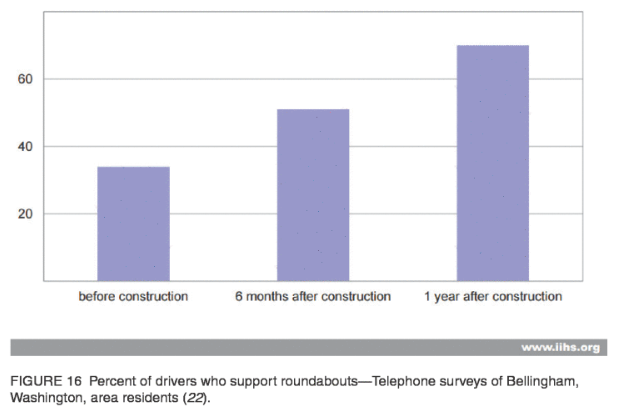

Research has shown many drivers can be skeptical of roundabouts if they’ve never driven through one before, but become supporters after construction is complete. Follow-up surveys conducted in six communities after roundabouts had been in place for more than one year found the level of public support increased to about 70% on average after construction. Another study showed that when two intersections near Bellingham, Washington, were converted to roundabouts, support for the roundabouts went from 34% before construction to 51% six months after, and 70% more than one year after.

The community engagement process has been the most difficult aspect of building roundabouts, especially for “those of us in the agency that saw the first ones proposed and constructed,” notes Walsh. But as more roundabouts are completed and the public becomes more receptive, newer projects benefit from the lessons learned during the earlier projects. – American Society of Civil Engineers

Costs and Maintenance

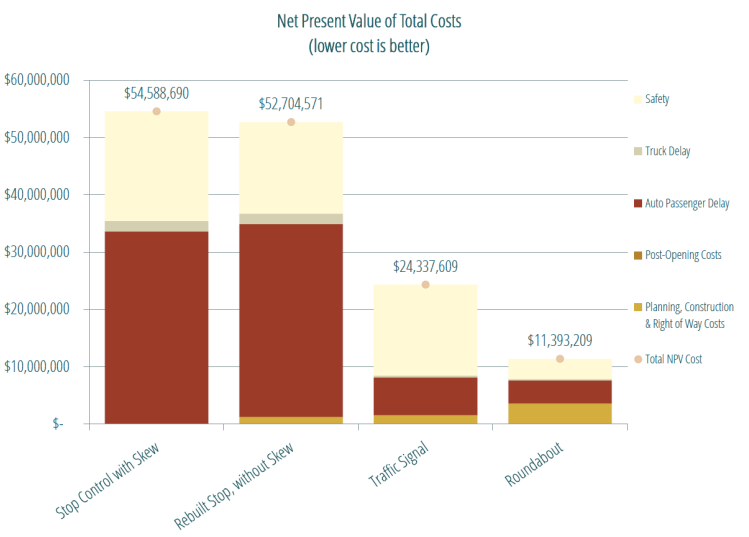

Traditional traffic signals can cost between $200,000 to $400,000 per intersection and can have annual maintenance costs of $8,000 or more. Roundabouts, depending on their size and other design variables, have a wider range of potential up-front costs, ranging from $200,000 to $3,000,000. Maintenance costs, however, are much less with roundabouts, as signal/conduit maintenance and repair are not needed. Power outages are much less of a problem with roundabouts as well, as police patrols or temporary stop signs are not needed during blackouts.

An analysis by MassDOT showed that when taking into account potential traffic delay, lifetime costs and other factors, roundabouts have a much lower net present value of total costs than signalized intersections.

Traffic Flow

Roundabouts can often improve traffic flow due to the reduction of stop and go traffic that’s often caused by signals, particularly in urban areas. Florida DOT states that roundabouts can increase intersection capacity by 30-50%. Another study found that capacity increased 67% compared to signalized intersections, average delay decreased 72% and 95th percentile queue dropped to 82.2%. roundabouts Combined with a reduction in overall traffic speeds which improves safety for all modes, roundabouts benefit not only vulnerable roadway users but drivers as well.

Studies by Kansas State University of 11 other roundabouts in Kansas concluded that the roundabouts reduced stopping, queuing, delay and so forth 50 to 90% as compared to signals. Also, for any given level of traffic, roundabouts generally operated at one level of service higher than a signalized intersection. So there is no doubt that roundabouts improve traffic flow, and it follows that improved traffic flow should be good for business. – A Study of the Impact of Roundabouts on Traffic Flows and Business

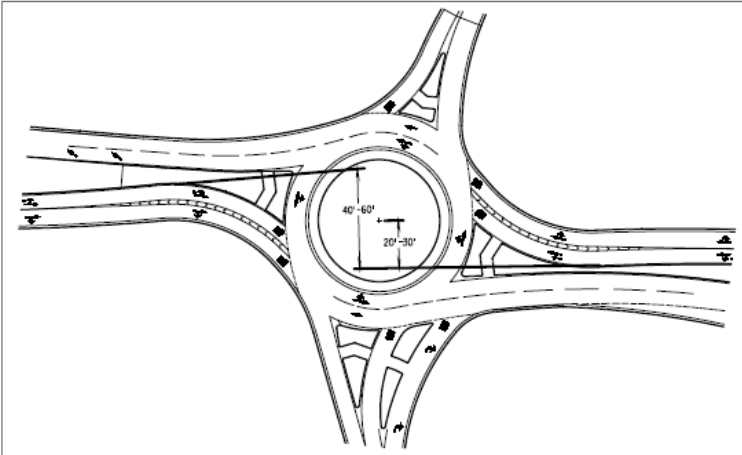

Roundabout Styles

While roundabouts must meet minimum design criteria based on engineering standards, their flexibility allows them to be constructed in a variety of neighborhoods, roadway classifications, and right-of-way widths.

Resources

TRB’s National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) Synthesis 488: Roundabout Practices

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2016. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/23477/chapter/3

MassDOT Roundabout Guide: https://carfreeamerica.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/dot-hwy_Roundabout_Planning_and_Design_Guide_Mar2022.pdf

FDOT Guide to Roundabouts: https://www.fdot.gov/agencyresources/roundabouts/benefits.shtm

FHWA Guide to Roundabouts: https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/intersection/roundabouts/

U.S. DOT Roundabout Informational Guide: https://nacto.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/Roundabout-An-Informational-Guide.pdf

Lincoln, NE Safety Guide for Roundabouts: https://www.lincoln.ne.gov/City/Departments/LTU/Transportation/Traffic-Engineering/Roundabouts/Benefits

Ourston Roundabout Design 101: https://carfreeamerica.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Roundabout-Design-101_-Principles-Process-and-Documentation-Part.pdf

City of Columbia Roundabout Guide https://www.como.gov/public-works/street-division/traffic-management/neighborhood-traffic-management/roundabouts/