Cities across the world are making a serious, coordinated effort to build new public spaces for cyclists and pedestrians in response to Coronavirus and related social distancing measures. Milan will add bike lanes and new pedestrian spaces to 22 miles of streets over the next year. It’s an attempt to head off a resurgence in driving as Italy recovers from the pandemic and creates alternatives to crowded transit vehicles. Denver has recently closed off a network of low-volume neighborhood streets to through traffic to give people space to exercise. Toronto implemented weekend, cyclovia-style road closures. A1A in Fort Lauderdale recently closed off a lane of traffic to expand the sidewalk along the beach, and Miami Beach closed off Ocean Drive to all automobile traffic.

Anecdotally, I’ve never seen more people riding bikes here in Miami. During the peak of the pandemic in April, cyclists were often riding on Biscayne Boulvard, normally a highway-like arterial filled with speeding traffic. As rush hour traffic disappeared, cyclists took their place. It could be argued that active mobility demand is artificially suppressed because of automobile traffic. If, say, only 15% of a street’s right of way is dedicated to active mobility, demand for those modes will be limited by the physical space allocated to them. Induced demand works in reverse as well.

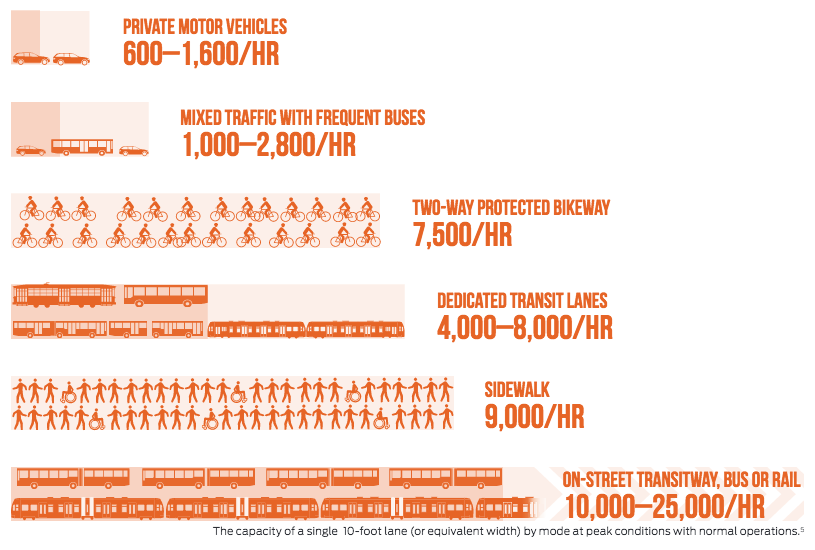

The most contentious issue in creating new spaces for pedestrians, cyclists and other non-auto modes is converting automobile lanes to other uses. There is only so much real estate available on a street, and though travel lanes can be narrowed sometimes, true street transformations often require the conversion of automobile lanes to other uses. Before the pandemic, driving rates bounced back from the 2008 economic downturn, with national total vehicle miles traveled at an all-time high. This time, things may be different. The public is noticing the tangible benefits of driving less. During the shut down, LA’s air quality improved dramatically. Bike shops are reporting very high demand for new bikes, and people who haven’t ridden a bike in years are realizing the benefits of cycling. More people will be working from home even after the pandemic is over as well. If most workplaces allow their staff to work from home even one day a week in the coming years, such a change multiplied across hundreds of thousands of employers will have an enormous impact on peak hour traffic volumes – the primary metric used to determine the feasibility of road diets and closures.

The pandemic has revealed that we’ve allocated far too much space to the most inefficient, unsustainable mode of travel. There are entire networks of redundant traffic lanes and excessively wide intersections that could be redesigned with minimal impact to traffic. Pandemic road closures, while taking place during a period of exceptionally low traffic volumes, are a great test run for more permanent changes. Tactical urbanism projects can create low-cost public spaces which encourage public support for more permanent changes. As traffic volumes start to increase, drivers may also grow accustomed to not having every 35 mph street designed like a highway. As usual, NACTO is on the forefront of design and recently published an implementation guide for low-cost street conversions which support public health and active mobility.

Travel patterns are also shaped by culture, and with so many commuting habits upended during the pandemic, large segments of the public may realize that sitting in traffic for several hours a day is not a good use of their time or money. When a critical mass of people becomes accustomed to spending less time commuting, grassroots support for street changes will grow. Increasing unemployment rates will also necessitate more affordable transportation options. With disposable income declining, automobiles are becoming a luxury which many can no longer afford.

Where does this leave transit? Stimulus funding is supporting operations of transit agencies which have been hit hard by the pandemic. As fear of the pandemic declines and new treatments become available, ridership will bounce back. An increase in telecommuting could make longer transit trips to and from work more acceptable for the (fewer) days which in-person office visits are required. Projects like NYC’s 34th St. bus lanes could also become a model for more cities looking to repurpose underutilized automobile lanes for dedicated transit use.

There has never been a better opportunity to transform our streets to support public health, active mobility and alternatives to automobile travel. When parks closed and traffic declined during the pandemic, necessity created new demand for people-oriented public places. Let’s hope the momentum created by recent street conversions becomes a permanent change in how we prioritize transportation options across the country.