I recently took Brightline to West Palm Beach and spent the afternoon cycling around the city. The new woonerfs at Clematis Street and City Place, designed by Dover Kohl, were filled with people and outdoor vendors. Automobile traffic speeds were comfortable and cars almost always yielded to pedestrians in crosswalks. From Clematis Street I turned south onto S. Dixie Highway, a 2 lane one-way street which I thought would be equally as comfortable to cycle on. Not quite. Traffic speeds were notably faster, drivers were more aggressive and seldom yielded to pedestrians at uncontrolled crossings. Since Clematis Street has built-in traffic calming features like textured pavement, I also cycled on more traditional two-way streets in the area for a better comparison. The difference in traffic speeds and cycling comfort was still dramatic, with two-ways being notably slower and more comfortable – not just while cycling but while walking, too.

My experience in West Palm Beach wasn’t the first time I’ve made these observations. I’ve tweeted about Miami’s fast 3 lane one-ways in Brickell and the confusing traffic movements where one-ways converge. Brickell is the densest, most urban neighborhood in Florida, yet many of Brickell’s streets act as traffic sewers which are inhospitable for anyone outside an automobile. Many downtown areas in the U.S. have multi-lane one-way streets since they became fashionable in the latter half of the 20th century.

In projects I’ve worked on in Baltimore, Dallas and other communities in Florida, I’ve noticed one-ways often had higher speeds, more crashes, and a far less qualitative sense of safety for vulnerable road users. I’ve heard a lot communities raise safety concerns about one-way streets during numerous public meetings I’ve attended. I’ve even heard drivers raise issues about circuitous navigation and confusing signage with one ways, particularly in denser urban areas. My personal and professional experience also leads me to believe that few people who actually use them as a pedestrian or cyclist actually like them. So why are they everywhere?

The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) Green Book has influenced the design of streets for the past few decades, and most traffic engineers will point you to this book to justify one way streets. The primary rationales it gives for one ways include:

- Removing the delay caused by left-turning cars and increasing traffic capacity and speed

- Fewer intersection conflicts and more efficient signal timing

- In theory, fewer and less severe crashes (e.g. by eliminating head-on crashes)

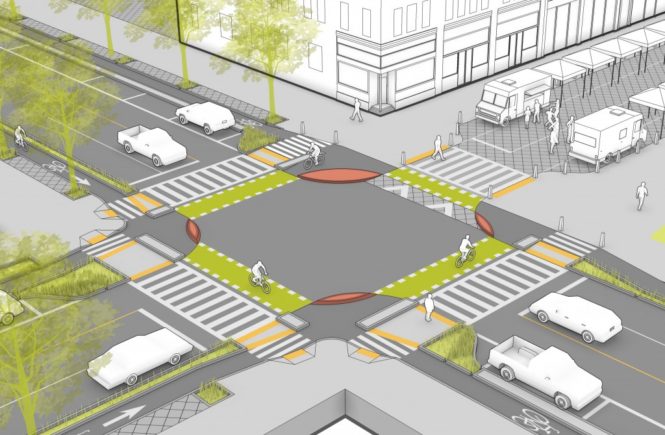

In a Synchro traffic model, these may make sense. It’s a different story out on the streets. Left turn vehicle delay actually increases pedestrian visibility and slows traffic to a safe speed. Fewer vehicle intersection conflict points is technically correct, but AASHTO fails to consider that having slower speed, property-damage only crashes is preferable to fewer higher-speed crashes which may result in injury or death. Conflict points may also not be a useful variable in determining real-world safety outcomes, as noted in The Boulevard Book. One-way streets also have far more pedestrian-vehicle conflict combinations, as described in the famous Walter Kulash research paper, “Are We Strangling Ourselves On One-Way Networks?” As for signal timing efficiency, I’ll get to that a bit later. The third point, fewer and less severe crashes, isn’t supported by real-world evidence. In fact, studies done in Louisville and Canada show conversion from one-way to two-way traffic decreases crash rates and improves safety for pedestrians. In my professional experience, I was involved in early conceptual work for the McKinney-Cole St. two-way conversion in Dallas, which has since progressed into design. The impetus for the conversion came from vocal community concerns about speeding traffic and severe automobile crashes on the one-way pair, many of which involved pedestrians.

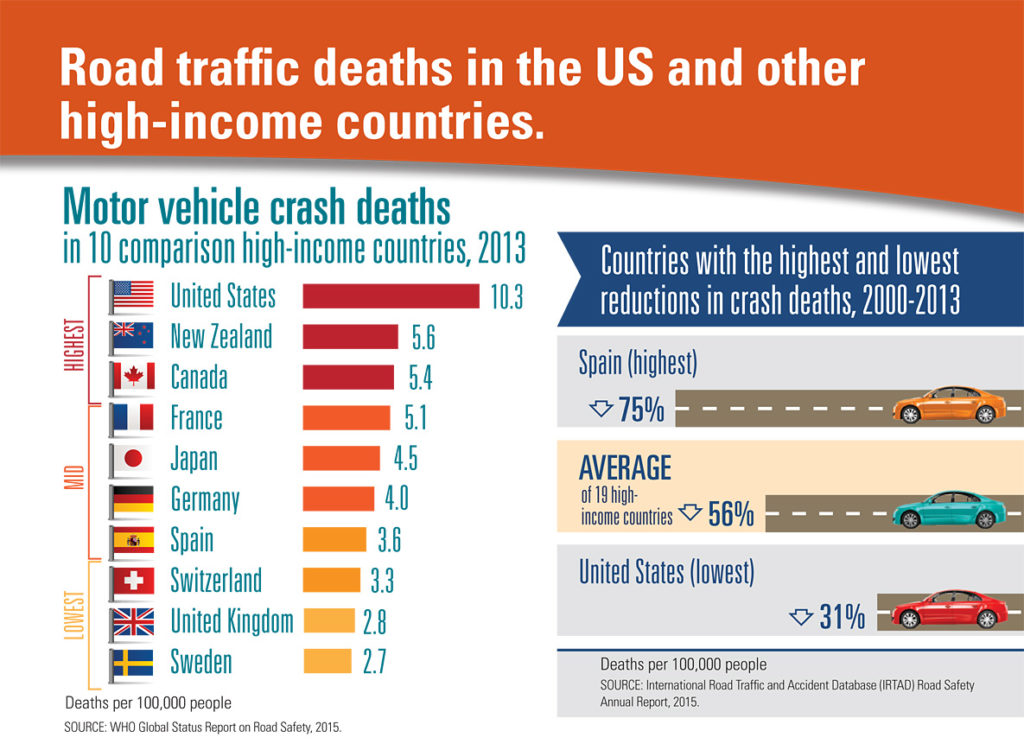

The fact that one-way streets essentially speed up traffic is often masked with terms like, “reducing delay”, “improving efficiency” and “increase capacity”. Even the claimed benefits of increased capacity with one-ways is questionable, with some studies showing that two-ways actually have more capacity. And unfortunately, enabling higher traffic speeds in any circumstance imperils roadway users and leads to more roadway injuries and deaths. The fundamental reason many urban one-way streets exist is because some traffic engineers and planners think surface streets should operate like highways – with as little interference in traffic flow as possible. This idea is partially responsible for making U.S. roadways the most dangerous of any developed nation.

There’s also the issue of intersection predictability which is seldom discussed. Most roadway users are used to two-ways, since most of our streets operate as such. For drivers, I’ve seen many vehicles drive the wrong way on one-ways because they didn’t see a “Do Not Enter” sign. Vehicles turning from a one-way onto a two-way might also not immediately realize they need to be on the right side of the road. Pedestrians crossing a one-way might not realize there’s traffic coming from the “wrong” direction. Left turning vehicles traveling in the left lane on one-way streets may take the turn at higher speeds, surprising pedestrians since opposing traffic on two-ways usually slows this left turning movement down. I won’t bore you with additional scenarios, but you can see how intersections become more complicated with one-ways. Mental models of how intersections work often need to be re-assessed with one-way streets. Why place that burden on roadway users? Streets should be predictable and intuitive as possible.

Sentiment against one-ways began in earnest about a decade ago, with many cities converting streets back to two-way, and many more currently planning for conversions . More recently, cities are converting a collection of streets to two-way traffic so these conversions work at the network level. While living in Dallas, I saw the transformation of Houston St. first hand when it went from a 4 lane one-way to a 3 lane two-way with protected bike lanes. Traffic slowed down, navigation for drivers became easier, and due to the road diet, space was freed up for new bike lanes.

Anecdotally, I heard the Houston St. conversion helped businesses in Dallas’ Victory Park neighborhood. Other case studies support this idea, with cities seeing increased retail sales on streets which were converted from one-way to two-way. Better store visibility because of slower, bi-directional traffic may make drivers more likely to stop and spend money in a neighborhood. Designing streets for local traffic instead of through traffic makes for a more pleasant shopping experience for pedestrians as well.

Now let’s talk transit. One-way pairs which include transit routes are often more circuitous and confusing for transit riders. Convenience and intuitiveness are key in making transit useful, and service running in both directions on the same street is the gold standard. NACTO provides similar recommendations in their transit guidelines, and states that two-way streets are inherently more transit-friendly than one-ways. There are circumstances where dedicated transit lanes can work well on one-way pairs, and two-way conversions aren’t always possible. In these cases, I’d rather have a one-way pair with dedicated transit lanes than with no transit lanes at all.

I’ve heard the argument that signal timing can mitigate traffic speeds and that signal synchronization is easier with one-ways. I find this argument both true and false. Signal synchronization can be simpler with one-ways, but trying to slow traffic speeds via signal timing assumes every driver understands the timing scheme and adjusts their driving accordingly. Otherwise, you’ll have frustrated drivers speeding up mid-block only to catch every red light, and then speed up again mid-block to make up for the time lost for catching every signal. Signal timing seldom deters mid-block speeding if a street inherently feels like it can accommodate high speeds to a driver. And one-way streets simply feel faster to drivers. This is another example of a traffic engineering concept that makes sense in traffic models, but doesn’t work as expected in the real world.

There are exceptions to every rule, and two-way conversions aren’t a panacea, but they can solve a lot of problems at minimal cost to cities (provided there aren’t many traffic signals involved – then conversions can get expensive). Some innovative engineers have tried to make one ways as people-friendly and safe as possible, though. This Strong Towns article has a good example, but the author’s ultimate conclusion that,”two-ways will simply gridlock at lower traffic volumes than one-ways. It’s physics.” is fundamentally flawed. Traffic engineering is less physics and more human behavior. Traffic models can often be wildly inaccurate, and people (or AI) will find alternative driving routes before surface streets become too congested. This vague, doomsday prediction of “gridlock” has been used for half a century as an excuse to widen our streets, disrupt our neighborhoods, speed up traffic and make our streets some of the most dangerous in the world. It seems avoiding gridlock always involves making our streets as fast and dangerous as possible. We need to find a better way.

Arguments on this subject will go on forever, but having lived in cities across the U.S. without a vehicle for the past decade, and then researching, helping design and experiencing all types of streets first hand, I’ll take two-ways every single time.

Research and Resources

Journal of Public Health

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10927849

“One-way streets have higher rates of child pedestrian injuries than two-way streets in this community. Future risk factor and intervention studies should include the directionality of streets to further investigate its contribution to child pedestrian injuries.”

Missoula , MT economic study – Missoula Redevelopment Agency

http://www.ci.missoula.mt.us/DocumentCenter/View/29737

Excellent summary of economic benefits of two way conversions for multiple U.S. cities.

“The economic analysis determined that a short-term benefit in sales of approximately 10% to 13% for downtown retailers could be expected from the conversion.”

Walker, Kulash, McHugh – Transportation Research Board

http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/circulars/ec019/Ec019_f2.pdf

Good run down of general benefits of two way conversions, including retail visibility and traffic safety.

“There are simply more (typically 30-40 percent) more vehicle/pedestrian conflicts within a one-way street network than in a comparable two-way system.”

Baco, Meagan – Clemson University

http://tigerprints.clemson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1595&context=all_theses

“Beyond, an increase in property values, the one-way to two-way conversion of Upper King Street, generated a new interest in the commercial properties along the street, increased pedestrian activity of the area because of increased safety and general attractiveness, and has acted as catalyst in the further preservation of the storefronts lining Charleston’s most recognizable street.”

University of Louisville

http://www.planetizen.com/node/69354

“The results were stunning. Two-way conversion improves the livability of a neighborhood by significantly reducing crime and collisions and by increasing property values, business revenue, taxes, and bike and pedestrian traffic. Outside consultants, with price tags of millions of dollars, never predicted this in places like Oslo, San Francisco, St. Louis, and Atlanta.”

Vancouver, Washington two way conversion

http://www.governing.com/topics/transportation-infrastructure/The-Return-of-the.html

“The merchants on Main Street had high hopes for this change. But none of them were prepared for what actually happened following the changeover on November 16, 2008. In the midst of a severe recession, Main Street in Vancouver seemed to come back to life almost overnight.