The tweet below inspired me to research residential zoning codes in other countries, and I found that almost every country has better residential zoning codes than the U.S. Especially Japan. This article is reposted from Urban Kchoze. I thought it was an interesting summary on how Japanese zoning differs from the U.S.

1- Zoning is a national law, not a municipal by-law

This might be the single most interesting characteristic of Japanese zoning that differentiates it from zoning in North America. Here, cities are essentially the sole masters of their zoning, they conceive it, adopt the bylaws and then apply them as they see fit. This isn’t quite wise considering how many cities, particularly smaller ones don’t really have the expertise to plan a city decently with euclidean zoning. In Japan, the national government created the zoning law, which it could do by mobilizing expertise to make a good set of laws.

That being said, cities aren’t completely cut off from the business of zoning. Though the law is adopted by the national government, its local application is left to city governments, as long as they respect the national law. So cities still have some power, but they have guidelines, which seems to me to be a good compromise. The only issue is that it eliminates possibilities of experimentation which could find better ways of doing things, as cities cannot try a different approach, they are bound by the approach established by the national government.

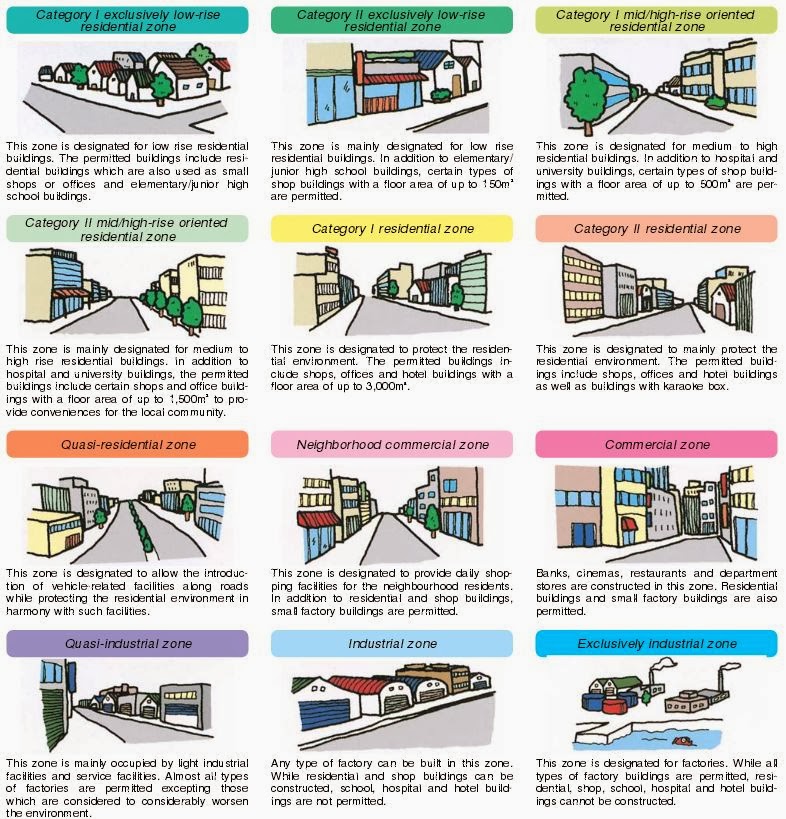

2- There are only 12 different zones

In North American zoning, there are often hundreds of different zones with different characteristics. In Japanese zoning, cities can only define 12 different zones, going from low-rise residential zones to exclusively industrial zones. There are certain variations between these zones, like the maximum ratio between the building’s area and the lot’s area, or the Floor-Area Ratio (ratio between the sum of floor areas of every story of the building to the lot’s area), but overall the rest of the zone, especially the uses allowed in it, are the same. The ratios I named just above are crucial to define what kind of density is allowed. And even though these maximum ratios can vary, cities can only select certain values.

For example, for Category I low-rise residential zones, cities can only choose a maximum ratio between the building and lot areas of 30, 40, 50 or 60%. The lowest possible maximum FAR (Floor-Area Ratio) is 50%. For comparison’s sake, in the Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu zoning I described earlier, following the rules, the maximum building-lot ratio is 33%, though in practice, it is generally about 20-25%, which is typical of Québec suburbs.

3- Zones still restrict uses, but they tend to allow a “maximum” use instead of an exclusive use for each zone

In North-American zoning, zones clearly specify which use is allowed on it. In general, zones allow only one or two uses. For example, a residential single-family detached home zone tolerates only single-family detached houses. Don’t try to put a convenience store or a school in one, nor a duplex. Similarly, multifamily zones allow only apartments, don’t try to build a house in one. In commercial zones, only commercial buildings are tolerated, any kind of residential use is prohibited. Etc…

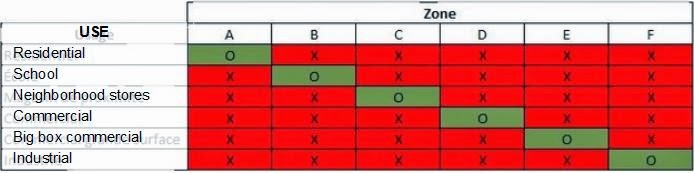

If we want to illustrate this principle of zoning with exclusive uses, this is what we’d get:

The columns represent different zones, the rows represent the different uses. When the square at the intersection of a certain column and a certain row is red, it means that the given use is forbidden in that zone, when it is green, that means that the use is allowed.

Note that I’ve put the uses in an order of increasing “nuisance”, the lower you get, the more the use is one we tend to want to separate from residential areas. Nuisance is a very loose definition, even just increased activity is considered “nuisance” because of the noise and circulation it brings about. That’s why schools are considered greater “nuisance” than residential areas, even if in fact we want to keep schools in residential areas, to keep kids from having to take buses to get to school.

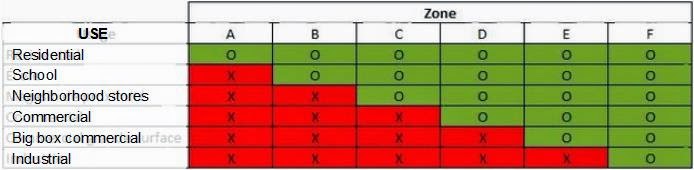

If we wanted to illustrate the principle of Japanese zoning in a similar way, we’d get something like this:

The difference is evident. There is a lot more green. That is because Japanese do not impose one or two exclusive uses for every zone. They tend to view things more as the maximum nuisance level to tolerate in each zone, but every use that is considered to be less of a nuisance is still allowed. So low-nuisance uses are allowed essentially everywhere. That means that almost all Japanese zones allow mixed use developments, which is far from true in North American zoning. Euclidean zones CAN allow mixed uses… but in practice, it is very rare that they do so.

This great rigidity in allowed uses per zone in North American zoning means that urban planing departments must really micromanage to the smallest detail everything to have a decent city. Because if they forget to zone for enough commercial zones or schools, people can’t simply build what is lacking, they’d need to change the zoning, and therefore confront the NIMBYs. And since urban planning departments, especially in small cities, are largely awful, a lot of needed uses are forgotten in neighborhoods, leading to them being built on the outskirts of the city, requiring car travel to get to them from residential areas.

Meanwhile, Japanese zoning gives much more flexibility to builders, private promoters but also school boards and the cities themselves. So the need for hyper-competent planning is much reduced, as Japanese planning departments can simply zone large higher-use zones in the center of neighborhoods, since the lower-uses are still allowed. If there is more land than needed for commercial uses in a commercial zone, for example, then you can still build residential uses there, until commercial promoters actually come to need the space and buy the buildings from current residents.

So in a way, regarding use restrictions, North American zoning tends to be “exclusive”, Japanese zoning tends to be “inclusive”

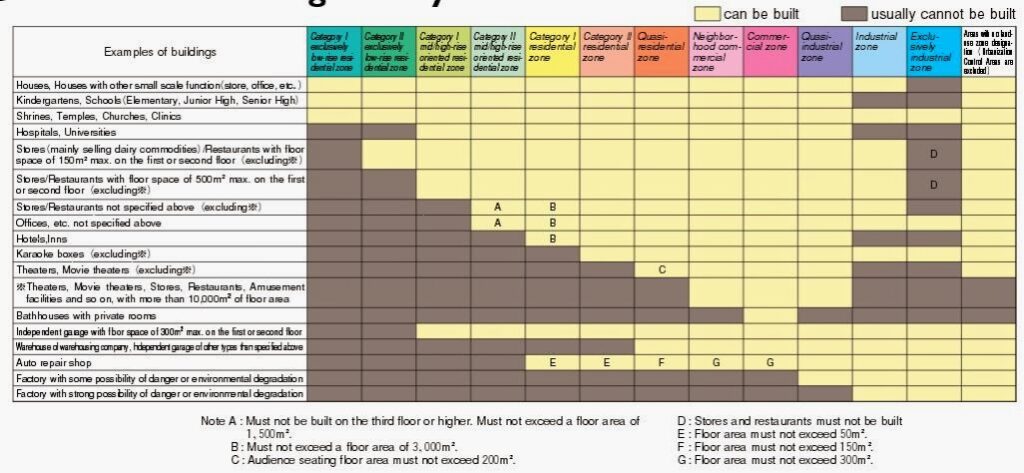

By the way, here is the actual image from the Japanese norms. As I said, when an use becomes allowed in a certain zone (yellow square), it remains allowed in all higher zones (squares to the right remain yellow). The only exception to that is the exclusive industrial zone, which is meant for heavy industry that is best kept separate from other uses.

Note that this means that when a city wants to zone for, say, big commercial stores, they are forced to allow a variety of “lesser” uses in the same zone.Same thing for offices, if they want to build offices, they must zone for at least a Category II mid-rise residential zone, on which the smallest maximum ratio they can put is 100% of FAR (but they can go higher, up to 500% FAR), which means in practice apartments with at least 3-4 stories. If they want to allow bigger offices, they must also allow bigger residential buildings and stores in the same zone. This “bundling” of uses imposes mixed use developments on cities.

4- Japanese zoning doesn’t differentiate the types of residential use

I already mentioned how North American zoning tends to treat single-family and multifamily as two separate uses to keep segregated. Even different forms of both can be treated as different uses, town homes can be forbidden even in single-use zones, duplexes can be banned from zones planned for apartment blocks. In Japan, there is no such segregation. Residential is residential. If a building is used to provide a place to live to people, it’s residential, that’s all. Whether it’s rented, owned, houses one or many households, it doesn’t matter.

This doesn’t mean that people can build 10-story apartment blocs in the middle of single-family houses (at least, not normally). As I mentioned, there are maximum ratios of building to land areas and FAR that restricts how high and how dense residential buildings may be. So in low-rise zones, these ratios mean that multifamily homes must also have only one to three stories, like the single-family homes around them. So in neighborhoods full of small single-family homes, you will often see small apartment buildings full of what we would call small studio apartments: one room with a toilet.

Once again, this type of zoning reduces the need of competence from urban planners to have a decent city. In North American cities, if the planning department doesn’t plan for enough multifamily or single-family zones, you can create big problems. There may be shortages of either multifamily or single-family zones, pushing prices up for that kind of housing. In practice, it’s most often rental units that get the shaft, resulting in sky-high rents as there is a rental unit crisis. In Japan, since they don’t differentiate between the two, people build what they actually need rather than what is commanded from above. And if there is not enough multifamily housing or that land is running out, pushing prices up, buying rundown houses and replacing them with multifamily housing is a sound business plan.

However, in practice, this largely means that multifamily homes tend to congregate around schools, commercial sectors or train stations. This makes sense, because as I said earlier, the revenues per square foot of land of multifamily uses is higher than for single-family homes. So multifamily promoters will tend to be willing to pay more per square foot and thus will beat single-family promoters for desirable lots, especially since multifamily residents will tend to favor proximity more than single-family residents.

5- It includes rational rather than arbitrary height limits

In North America, the number of stories buildings can have is limited, but these limitations are completely arbitrary. For instance, if buildings in a zone have 2 stories maximum, then there is likely going to be an height limit of 2 stories put on the zone. Why 2 stories? “Because that’s what is built here, so that’s what you can build”. The height limits make no sense.

Now, there is a reason why one would do height limits. Height limits to allow the sun to shine on the street makes sense, and one can argue that you need some space between buildings to allow some air flow. Those are defensible arguments for height limits… but they do not justify the arbitrary limits put in place in North America. When houses are separated by 80-90 feet, don’t pretend that you absolutely need to limit buildings to 2 stories for “air flow” or shadow avoidance!

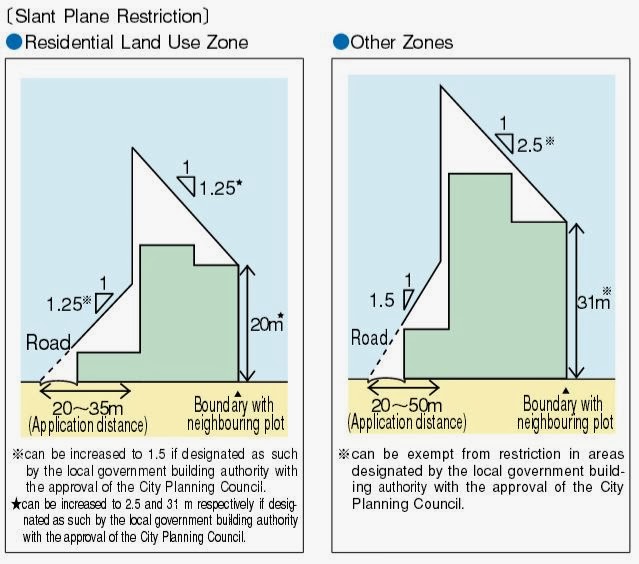

In Japan, the height limit that exists make sense, it’s an easy rule that can be applied everywhere, it’s easier shown than explained:

So, the farther the building is set back from the street, the higher it can be. The wider the street, the higher the buildings that can be built next to it. These rules are sometimes omitted from certain places where they want to build higher buildings, like offices in skyscrapers for instance.

Note that this guideline also exists in North American cities, but is often bypassed by arbitrary height limits written in every zone..

6- Cities still conserve the right to require certain geometric criteria

Despite the national guidelines, cities aren’t completely powerless. They can identify zones where certain rules will be waived to allow higher densities, or alternately, establish certain criteria like a minimum quantity of green spaces on each lot, minimum setbacks, etc… But the basic rules of zoning are still defined by the national government.

Conclusion

This was simply a description of another zoning model to show how things can be done differently.

Personally, I believe these practices make a lot more sense than the current standard zoning practices in North America. The creation of a national law establishing a limited number of zones is, in my opinion, a great idea, as well as the elimination of the single-family/multifamily distinction and the inclusive zoning for uses rather than one-use zones. Using general rules to solve problems regarding sunlight instead of allowing cities to put arbitrary limits on height is an excellent idea. When you have a problem, the rules must be set up to directly solve the problem and be universal rather than arbitrary numbers which only have a loose connection to the actual problem.

In short, Japan’s zoning laws are more rational, more efficient and just plain better than what we do now.

Now, this isn’t the only model around. New Urbanists push for form-based zoning to favor walking and to allow mixed used developments. Houston in Texas is known as a city without zoning because it doesn’t restrict land use through its planning agency, anything can theoretically be built anywhere (though there are private covenants that limit what land can be used for and there used to be stringent minimum lot and minimum parking rules that severely restrained density).

What’s important to take away is the incredible mess that our indefensible euclidean zoning has made of our cities and that there are many better ways to zone our cities that are out there. The question isn’t whether we should change our zoning laws or not, it’s how they should be changed.