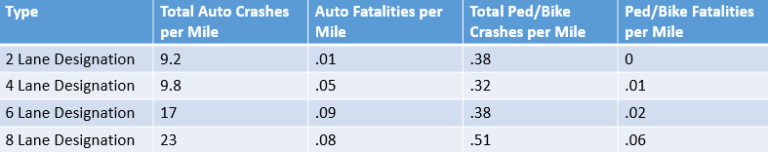

Yes, I said it. I was recently reading a draft of a city’s Vision Zero plan. It mentioned that a substantial number of fatalities and injuries occurred on state routes. In my own research, I found the same trend again and again. Lots of crashes of all types on wider, faster streets. And many of these wide, fast streets are controlled by state DOTs.

State DOTs control many surface streets in cities due to a mix of historical factors, regional transportation coordination needs, and the higher traffic volumes of these streets. This is all well and good. However, many roads that were once local or county roads were taken over by state DOTs during the mid-20th century, especially after the establishment of the Interstate Highway System. The goal was simple: Move traffic as quickly as possible to and from interstates. Pushing more traffic through surface streets, many in urban areas with vulnerable road users and nearby parks and schools, was the priority during the 20th century.

Take, for example, Roosevelt Boulevard in Philadelphia.

Aware of the road’s shortcomings, city officials have long sought design changes that would reduce crashes. But they are powerless to act on their own, because the boulevard is controlled by the state of Pennsylvania.

That situation is common across the United States, where many of the most deadly, polluting, and generally awful urban streets are overseen by state departments of transportation (DOTs). Often they were constructed decades ago, when the surrounding areas were sparsely populated.

Although only 14 percent of urban road miles nationwide are under state control, two-thirds of all crash deaths in the 101 largest metro areas occur there, according to a recent Transportation for America report. – Vox Magazine

With increasing roadway fatality rates due to a plethora of factors, FHWA and many state DOTs have made safety a priority. And a big part of safety is roadway design. While many state DOTs have constructed excellent safety projects which reduced fatalities, the timeline for projects is long and the need is great. The added bureaucratic layer of redesigning a state road also slows things down, especially when a project includes streets belonging to multiple jurisdictions (state and county or state and city). MPOs often make safety and complete streets a priority, but MPO priorities often don’t filter up to state DOT long range plans. A lot gets lost in translation.

State DOTs also have a lot of other responsibilities and oversee state-wide transportation systems. The nuances and community needs of some half mile state road running through some neighborhood often takes a backseat to, say, maintaining hundreds of miles of interstates or dealing with major national emergencies. When an agency is responsible for so much infrastructure over such a large area, even well-meaning DOTs find it difficult to act as a local transportation planning agency for much needed safety and complete street projects.

What’s the solution? Some DOTs have given their streets to cities, allowing more responsive street design. These projects are few and far between, however. But if a new national program were created, is this something that can be broadly applied across all 50 states and to hundreds of cities? If states did systematically give some urban streets back to cities, it would have to come with major funding increases. Difficult, but not impossible. Cities have far less transportation funding than states, though, and states share only 14% of transportation funds with their cities. Funneling more transportation money to municipalities (which, some say, is already owed to cities given how much they contribute to gas tax revenue and economic development) could be a long term policy goal to help accelerate safety projects on wide, fast streets – exactly the places where we need safety projects the most.

What would this look like at the national level? If formulas were changed to allocate more money to cities, cities could then apply to state DOTs to take over the most problematic state roads. Application criteria could include:

- Crashes: The more serious injuries and fatalities, the higher the ranking.

- Land uses: Schools, retirement communities, parks and other pedestrian trip generators nearby would increase the ranking

- Number of lanes: The higher the number, the higher the ranking

- Pedestrian/bike/e-mobility traffic counts

- Planning: A completed road safety audit with identified safety countermeasures would be required

Candidate state roads would be ranked, with the highest ranked given priority for this new funding. The state road, along with a percentage of new funding contingent on completing safety measures within a certain time frame, would then be transferred to the cities.

A new national program does seem like a heavy lift, but given the number of crashes on our state roads, particularly in urban areas, big problems call for big solutions. This program would also free up state DOT staff for bigger, more regionally significant projects while reducing their role in local planning issues – planning work that is more appropriate for municipal staff. State DOT focus could then shift exclusively to regional projects.

Let me know your thoughts on X. I’m thinking out loud here. @CompletedStreet.