The American Planning Association recently put out a comprehensive guide on shared mobility. You’re most likely familiar with the concept: Short term access to a mode of transportation on an as-needed basis. Think Zipcar, Uber, bike share, product or food delivery services, and soon, self-driving cars which will circulate through neighborhoods autonomously while picking paying passengers up.

There are a number of impacts shared mobility services will have on planning policies. Transportation, zoning, urban design and economic development will all be affected. While many zoning codes already include density bonuses or parking reduction allowances for incorporating shared mobility vehicles into development projects, transportation and urban design policies have often not kept pace with these new services. New shared services will influence complete street design, municipal parking requirements, and building access design in the decades to come. Here are a few issues I see which will need to be addressed in cities around America in order to address shared mobility:

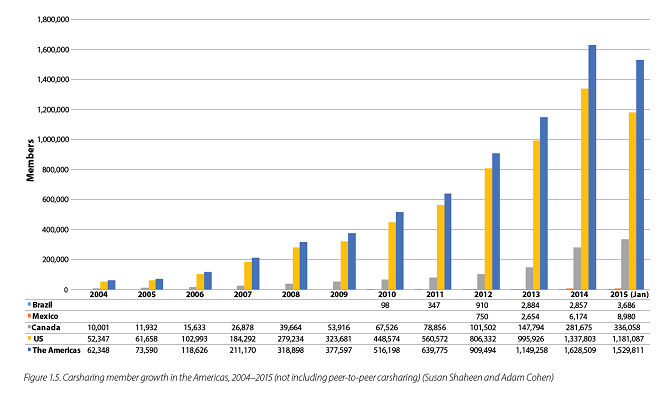

- Philosophy and Policy. Dedicating street right-of-way to car share vehicles has been done in cities throughout the country, but there are still legal hurdles and philosophical debates on whether car sharing should be treated as a public good or a private good. Given that car share services result in lower car ownership rates and lower per capita VMT, I lean towards considering the service a public good. This means that while car share companies are for-profit businesses, cities should still be able to justify marketing, right-of-way dedication, and other small expenses for promoting shared mobility services in an equitable way to the public.

- Parking. There are several factors which may necessitate a substantial reduction in public and private parking requirements. Generation Z are getting drivers licenses at astronomically low rates. On demand ride hailing services like Uber are filling in gaps between transit networks. No car households are becoming more common. Bike share systems and bike infrastructure are becoming more robust. As stated earlier, many cities already include parking reductions in their code in exchange for shared mobility services incorporated within or adjacent to a private development, and many cities have already eliminated parking requirements. In terms of complete streets, on-street parallel parking is often a feature in many roadway designs for obvious reasons. This constitutes valuable real estate and there are often trade offs between parking and other complete street components such as bike lanes or wider sidewalks. The amount of dedicated right way of given to parking may be reduced in years to come due to shared mobility use.

- Drop Off Areas. While parking needs may lessen, the need for dedicated drop off/pick up areas will grow. See that group of 8 people staring at their phones on the corner in Deep Ellum? They’re probably waiting for their Uber ride. Future complete street projects may want to incorporate dedicated drop off areas or exchange some parallel parking spots for shared mobility services. For large private development projects, drop off areas need to be considered at the earliest stages of design and incorporated in such a way that these areas don’t conflict with traffic flow, bike lanes or block sidewalks.

- Passing Lanes. Complete streets usually means the minimum number of auto traffic lanes. Cities may need to rethink this policy in the future. If a street goes from a 2 lane one way in a dense residential neighborhood to a 1 lane in order to accommodate a bike lane, this leaves a single lane for traffic and queuing for ride share services. Will local neighborhood drivers be OK with this? Does the community understand this trade off which wasn’t much of an issue even 3 years ago? These are questions that will need to be asked during the planning process. Likewise, converting 2 lane streets from one way to two way operation has traditionally been seen as a fundamentally good thing in planning circles. Drop offs and passing traffic around shared mobility vehicles now need to be considered with these conversions, especially in dense urban neighborhoods.

- Design Speeds. Finally, it’s well accepted that slower traffic speeds are better for neighborhood livability and safer for everyone. While this has more to do with autonomous vehicles vs. shared mobility, there’s some overlap. Self driving ride sharing vehicles use sophisticated cameras to read the road around them. This means its AI system will detect roadway width, vertical deflections and other features designed to slow traffic down. Designing for lower target speeds may be even more effective with autonomous vehicles and lead to greater speed compliance, but the jury is still out. My bet is that lower design speeds (versus lower posted speeds) will still be an effective way to slow cars even if self driving cars detect local speed limits. The pedestrian/cyclist comfort and safety benefits of right sizing a street are numerous anyway, and it will be quite some time, if ever, before 100% of vehicles are driven by HAL 9000.